"Lend-Lease" was a government program through which the United States supplied its allies in the Second World War with military equipment, technology, food, medical equipment and drugs, and strategic materials, including petroleum products. The main partners of the United States were the countries of the British Commonwealth of Nations and the USSR.

What is Lend-Lease?

Human memory is not limitless and weakens over the years. Even in the memory of an entire nation, with the passing of the wartime generation, the events of war become shrouded in haze, making it difficult to discern all its details, and perhaps even its essence. This is not only a matter of human psychology, nor solely the realm of historical science, which over time offers various interpretations of wartime events. In addition to these circumstances, there are external factors that weigh on people's consciousness, shaping their understanding of the past, which may not correspond even to what individuals themselves knew and thought about some time ago. These factors are to be found primarily in the realms of politics and ideology.

Looking at the history of the Second World War from this perspective, it has long become an arena of a real "war of memories," a clash of different interpretations of the war that have formed among individuals and entire nations. Already during the war, the governments of warring states were concerned about how this war would be portrayed in history, what would be ingrained in people's minds regarding who was to blame for the outbreak of this global conflagration, what character the war assumed for each country, who fought how, and what contribution was made to Victory and to the post-war world order, and so on.

Back in March 1943, the US Ambassador to Moscow, W. Averell Harriman, sharply criticized the Soviet side at a press conference, alleging that they did not show proper gratitude to the United States for Lend-Lease aid. "The Russian authorities," he said, "seem to want to conceal the fact that they are receiving assistance from abroad. Obviously, they want to convince their people that the Red Army is fighting this war alone."

It is believed that the ambassador was prompted to make such remarks because Stalin's order on the anniversary of the creation of the Red Army did not mention assistance from allies. The Soviet leader stated that "due to the absence of a second front in Europe, the Red Army bears the full brunt of the war alone." He further emphasized their own efforts: "The Soviet Union is increasingly deploying its reserves and becoming stronger."

After 1945, the competition in myth-making only intensified. If we take extreme interpretations of the Lend-Lease issue, for some, it might have been an important but not the decisive factor in Victory. For others, it "saved" the Red Army and was the decisive reason for the USSR's ultimate triumph. During the Cold War years, the Soviet Union sought to silence or minimize mentions of Lend-Lease and its significance for Victory. Shortly after the war, a book by N. A. Voznesensky, "War Economy of the USSR during the Great Patriotic War," set the tone for how the Soviet side subsequently assessed Lend-Lease. The author noted that "the military efforts of the United States of America and England... along with the Soviet state... served the cause of the liberation war," and a large number of military equipment produced in American factories "facilitated the defeat of German imperialism." As for the military-economic cooperation of the three leading powers of the anti-Hitler coalition, the book stated that in the USSR "during the wartime economy... the import of goods increased almost fivefold." Moreover, "the increase in the import of goods (mainly raw materials and materials) occurred due to deliveries by the allies of the USSR... However, if we compare the size of deliveries of industrial goods by allies to the USSR with the volume of industrial production in the Soviet enterprises during the same period, it turns out that the share of these deliveries relative to domestic production during the wartime economy was only about 4%." In another section of the book, Voznesensky extensively discussed how the war economy of Nazi Germany relied on the exploitation of the productive forces of almost all of enslaved Europe. In contrast, he emphasized the "techno-economic independence of the socialist economy from capitalist countries," without mentioning the extensive deliveries of Lend-Lease goods to the USSR and their role in ensuring the economic victory over the enemy.

Initially, the author intended to give a more detailed characterization of military-economic assistance from the allies: "Undoubtedly, the weapons, strategic materials, and food received by the Soviet Union from the allies contributed to the successful completion of the war against the common enemy – Nazi Germany. However, the defeat of Nazi Germany by the Soviet Army was mainly accomplished with domestic Soviet weapons and military equipment." However, these two sentences did not survive in the book. Stalin, having read the work in advance at Voznesensky's request, apparently under the influence of sharply cooled relations with yesterday's allies, struck out the mention of food, then crossed out the entire text and wrote in the margins: "Not that" (This is recounted in the memoirs of economist and publicist L. A. Voznesensky, the nephew of N. A. Voznesensky). So in the end, the book remained with the sole passage mentioned above, directly indicating deliveries to the USSR (but without mentioning the term "Lend-Lease").

Since then, the phrase contained in this passage and becoming a classic formula – "only about 4%" – has consistently been mentioned in the Soviet Union whenever Lend-Lease is discussed. However, it is worth noting the following. Very often, the figure of 4% denotes the share of all deliveries to the USSR relative to its own production. It is not specified what "production" is meant. Is it only industrial? Or does it also include agriculture (since the Americans supplied food to the USSR during the war)? Other variations are also encountered, for example, 4% of "all expenditures" of the USSR on the war. Meanwhile, Voznesensky mentioned 4% specifically in relation to deliveries of industrial goods to the USSR, and regarding raw materials and materials, he specifically noted a fivefold increase in their import from allied countries. Following the 4% mentioned in the late 1940s in foreign and then domestic literature, figures two to three times higher appeared. Comparing these different figures is difficult, if not impossible, because sometimes they refer to different things, and often the data on which the conclusions were based and the methodologies used for counting are unknown. In addition to the canonical 4%, the following data were often mentioned during Soviet times: out of the total Lend-Lease expenditures of the USA amounting to $46 billion, the share allocated to the USSR was $9.8 billion (while the British Empire, for example, received $30.3 billion).

In modern literature, different estimates are encountered. The total value of deliveries from the USA to the USSR is determined to be $11.3 billion. In addition, from Great Britain under the Lend-Lease scheme, goods worth $1.7 billion were received, and from Canada – $200 million. In total, the overall amount of all deliveries to the USSR under Lend-Lease amounted to $13.2 billion. The proportion of Lend-Lease in the total volume of industrial production in the Soviet Union was at least 7% (taking into account inflation in the USSR and the USA in 1942). However, it is necessary to consider the quality of Western technology and the bottlenecks in the Soviet economy. The discrepancies in the figures, which may confuse the reader and raise doubts about the correctness of the calculations, do not necessarily stem from a desire to exaggerate or downplay the significance of Lend-Lease and, accordingly, inflate a myth about it. It is necessary to clearly define what to count (ordered, produced, accepted, shipped, received), over what period (should shipments before the implementation of the Lend-Lease regime in the USSR be included, for example), from which sources (only from the USA or also from Great Britain and Canada). And do not forget about the system of weights and measures (long, short tons, etc.).

The inherent tendency of the Soviet era not to emphasize, but rather to downplay the importance of Lend-Lease did not mean that nothing was known about military-economic aid from Western powers to the USSR. Not only because in the post-war decades there were millions of living witnesses to this aid. Lend-Lease was also written about in multi-volume works on the history of the Second World War and in a number of monographic and other publications. Nevertheless, distorted perceptions of this issue existed in Soviet times (and are still encountered today), which can be called myths. Let's consider some of them.

The myth that Lend-Lease was invented for the Soviet Union and was paid for with Soviet gold is untrue.

In reality, the USSR had no connection to the inception of Lend-Lease. As early as 1940, there was awareness on both sides of the Atlantic that the principle of "pay and carry," initially used for American supplies to Britain, would soon become inapplicable because London would soon have no means to pay. The first experiment of providing supplies without payment involved transferring 50 World War I-era destroyers to the British in exchange for strategically important British bases in the New World. However, a more comprehensive and long-term assistance scheme was needed for countries fighting against the Axis powers. President Franklin D. Roosevelt metaphorically explained how to do this at a press conference in December 1940: "If your neighbor's house is on fire and you have a garden hose, lend it to your neighbor until his house is no longer burning and yours is in danger. When the fire is out, your neighbor will return the hose to you, and if it is damaged, he will pay for it when he has money." By helping others extinguish the already raging fire of the world war, Roosevelt envisioned that the United States would become the "arsenal of democracy." Eventually, a model of aid provision to countries subjected to aggression was developed based on supplying them with everything necessary for waging war (weapons, equipment, industrial machinery, vehicles, fuel, metals, food, medicine, information, etc.) on a lend or lease basis (hence "Lend-Lease"). However, this was contingent upon the defense of these countries being "vital" for the defense of the United States itself. On March 11, 1941, the Lend-Lease Act (An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States) was passed. On the same day, Roosevelt signed orders for the transfer of 28 torpedo boats to Britain and 50 75-mm guns and several hundred thousand shells to Greece.

It is clear that in the spring of 1941, Lend-Lease was not associated with the Soviet Union, which was then viewed in the United States more as an accomplice of Hitler than as his opponent in need of support. Therefore, there were even demands to include in the Lend-Lease Act a list of countries whose assistance could only be provided with additional approval from Congress, where there were strong anti-Soviet sentiments at that time. However, Roosevelt managed to retain flexibility regarding potential supplies to the USSR in the future. However, even after the Soviet Union was attacked by Nazi Germany, it did not immediately receive support on Lend-Lease terms. On June 24, 1941, speaking at a press conference, Roosevelt stated that the United States would provide "all possible aid" to Russia in its fight against the Nazis but laid out several conditions and avoided stating that it would be provided in accordance with the Lend-Lease Act.

Since the summer of 1941, American goods were delivered to Soviet Far Eastern ports. Soon, Americans also participated in Arctic convoys. A. Harriman represented the USA at the Moscow conference from September 29 to October 1, dedicated to organizing inter-Allied supplies. However, the official Lend-Lease regime was extended to the Soviet Union only on November 7, 1941. Although retroactively, counting began from the signing of the Moscow Protocol on October 1. On June 11, 1942, the USSR and the USA concluded an Agreement on the Principles Applicable to Mutual Aid in the Conduct of the War against Aggression. This document regulated Lend-Lease shipments and became one of the most important agreements signed by the Soviet Union and the United States during the war years. Alongside the earlier Soviet-British alliance treaty, it marked the final formation of the anti-Hitler coalition. Britain announced its intention to supply goods to the USSR under conditions similar to Lend-Lease in September 1941, even before the Americans. Canada directly joined shipments to the USSR from 1943 (prior to this, its products were counted within the British quota). Discussions on the internet about the Soviet Union paying (with gold, no less!) for all the weapons and other cargo sent to it by Western powers during the war is one of the main myths of Lend-Lease.

The question of who owed whom and how much, and how much was ultimately paid, is highly politicized and evokes very emotional reactions. Let's set aside the issue of post-war settlements in this case. It should be emphasized that during the war, no one had to pay for Lend-Lease supplies. And after the war, destroyed, lost, or used materials during combat were not subject to payment. The remaining property could be returned to the Americans upon their request, and if suitable for civilian purposes, it was intended to be fully or partially paid for based on long-term loans provided by the United States. Some reservation can only be made regarding the so-called "reverse lend-lease," that is, the provision of goods and services needed by the USA from recipient countries of Lend-Lease aid. However, in the case of the USSR, this "reverse lend-lease" (supplies of manganese and chrome ores and some other traditional items of Soviet exports, servicing American ships in Soviet ports, etc.) was expressed in relatively small quantities, unlike, for example, Britain. The USSR paid in cash or gold for deliveries from Western countries, ordered before or outside the Lend-Lease program. Talks about "Soviet gold" apparently draw on the history of the British cruiser "Edinburgh." This ship, as part of convoy QP-11, left Murmansk carrying about 5.5 tons of gold. It is believed that partly it was intended to pay for Soviet purchases outside the Lend-Lease program, partly it was precisely "reverse lend-lease": raw materials for gilding various telephone, radio, and navigation equipment produced according to Soviet orders. The cruiser was attacked by the Germans and sank in the Barents Sea on May 2, 1942. In the 1980s, almost all the gold from the "Edinburgh" was recovered and divided between the USSR, Great Britain, and the English company conducting underwater operations.

Another common myth about Lend-Lease is that the main, if not the only, supply route to the USSR was the northern route through the Arctic seas.

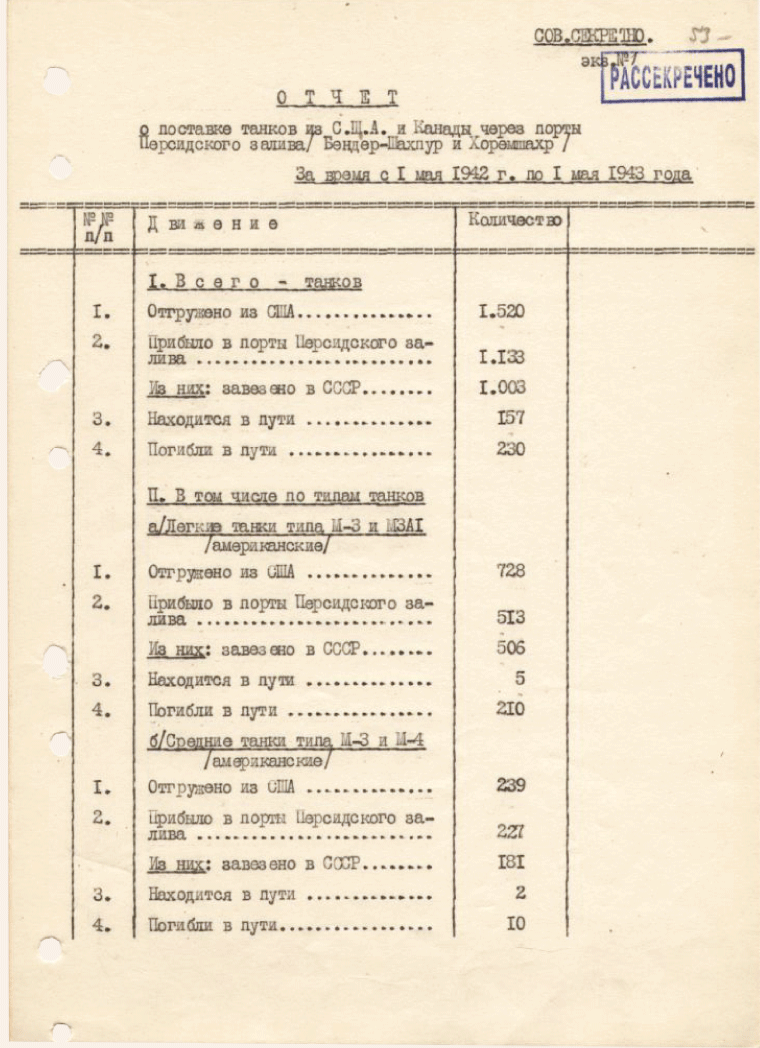

This route through the northern seas to Arkhangelsk and Murmansk, thanks to literature, cinema, as well as the memories of convoy participants, is undoubtedly the most well-known to the general public, but by no means the main one in terms of the volume of transported goods. This is evident from the table provided below:

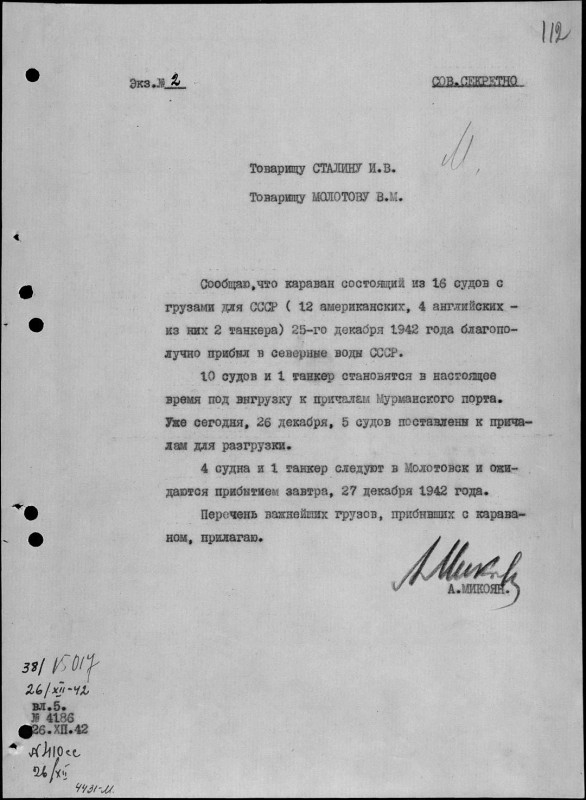

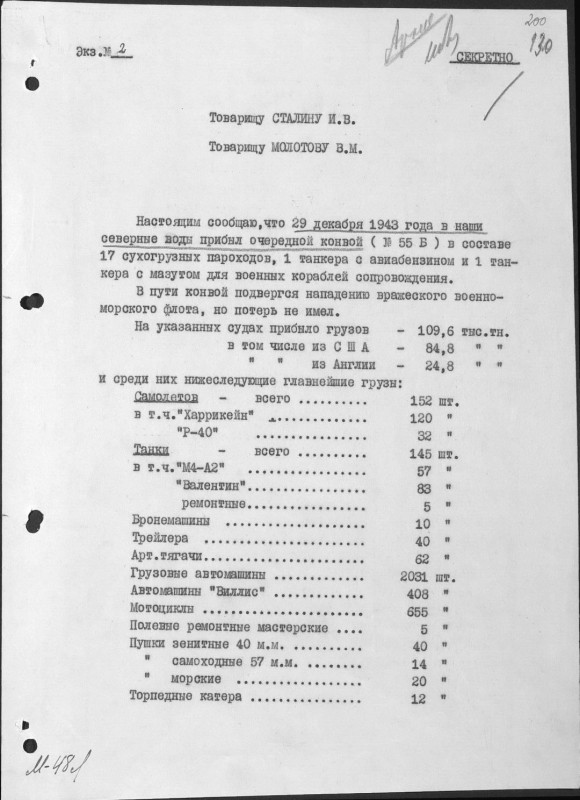

The Arctic convoys are also referred to as "northern," "polar," "Murmansk," or "Allied" convoys. This route was the shortest, fastest, but also the most dangerous. It traversed challenging navigational waters, but the main challenge was defending against constant enemy attacks. Convoys were initially formed in Scotland or Iceland. The British Admiralty was responsible for escorting and safeguarding the convoys. Merchant ships, accompanied by escort warships, usually sailed between the ice edge and Bear Island in the summer and south of this island in winter. Then the convoys entered the operational zone of the Soviet Northern Fleet, which, despite its modest capabilities, participated in protecting the cargo ships. After 10-14 days, the convoys arrived in Murmansk, Arkhangelsk, or Molotovsk (modern Severodvinsk). These northern (as well as Far Eastern) ports had to be urgently reconstructed to handle the huge volume of cargo. Land-lease materials were then transported by rail to the front lines and rear areas of the USSR, while the unloaded transport ships regrouped into convoys for the return journey. In 1941, the Arctic route accounted for approximately 40% of all deliveries. From 1942 onwards, the main flow of goods shifted to the Pacific Ocean and the Persian Gulf.

The first British convoy arrived in Arkhangelsk on August 31, 1941. Six more convoys arrived by the end of the year, all without losses because, contrary to common beliefs, the Germans initially showed little activity in the Arctic. However, in 1942, the Germans launched a real hunt for Allied convoys, sinking 69 transports out of 85 they managed to destroy in this area throughout the war. The tragic story of Convoy PQ-17 is well known. For an inexplicable reason, the British withdrew their escort, and as a result, 23 out of 36 ships were sunk. The heavy losses prompted the British to halt convoy shipments until the onset of the polar night. From March to November 1943, convoys did not sail again. In both cases, this caused serious tension in Allied relations because the northern route was the fastest way to deliver weapons to the USSR. And these interruptions occurred precisely during periods of heightened tension on the Soviet-German front. The British explanations did not seem convincing to the Soviet leadership. In total, from 1941 to 1945, 811 ships arrived in northern USSR as part of 40 convoys. The number of sunken ships was 98. Allies lost 16 warships. Over 3,000 sailors perished.

The Pacific route, which transported almost half of the cargo volume, turned out to be the largest in terms of cargo transported, although until recently, it was not widely known. The geopolitical position of the USSR in the Pacific Ocean was extremely disadvantageous at the time. Japan controlled all the straits leading to the ports of Soviet Primorye. Ships had to navigate through shallow, ice-filled narrow straits to avoid minefields. After the full-scale war in the Pacific Ocean began in December 1941, the situation with cargo transportation to the USSR became much more complicated. Now only ships under the Soviet flag with Soviet crews could operate here. Within 18-20 days, ships from the US West Coast reached the Far Eastern ports of the USSR without any escort. The Soviet side's shortage of tonnage was largely compensated for by deliveries from the US under lend-lease - 38 Liberty-type ships, standardized transport vessels built using assembly-line methods. The delivered cargo - mostly machinery and equipment, food, and petroleum products - was then transported by the Trans-Siberian Railway to the European part of the USSR. Often, rolling stock obtained from the US under lend-lease was used for this purpose.

Soviet ships in the Pacific Ocean were subjected to inspection and detention by the Japanese on numerous occasions. A total of 178 Soviet ships were subject to inspection, and some were detained for months. Eight ships were sunk by the Japanese. Several transports were destroyed by unidentified submarines, and about a dozen perished under unclear circumstances.

Another little-known route to the general public was the Trans-Iranian, or "southern," or "Persian corridor." Through Iran and the Caspian Sea, as one Iranian diplomat put it, a "safe backdoor" could be organized for deliveries to Russia. The Trans-Iranian Railway, which had access to the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea, could be utilized for this purpose. The English and Russians began discussing this issue literally from the first day of the Great Patriotic War. This was compounded by the need to prevent Iran from sliding into the Axis camp, which required the elimination of the German "fifth column" in that country. These two crucial issues laid a solid foundation for joint action by the USSR and Britain, although each side also pursued its own interests in the region. Tehran's refusal to neutralize pro-German forces in the country and reluctance to permit transit through its territory for weapons destined for the USSR compelled Moscow and London to take action. On August 25, 1941, Soviet and British troops were deployed to Iran. It is worth noting that the Soviet Union had full legal rights to do so under the Soviet-Iranian Treaty of 1921. Iran's weak transportation infrastructure initially hindered the organization of extensive deliveries to the Soviet Union. The British initially took responsibility for its reorganization and expansion. However, London clearly lacked resources. In 1942, the United States assumed responsibility for cargo transit to the Soviet Union. The number of American military and specialists in Iran reached 30,000 by the end of the war. Under the guidance of Western engineers, railways and ports were reconstructed, and roads were built in Iran. Americans built several automotive and aircraft assembly plants in Iran. Over 184,000 trucks assembled at these plants were sent fully loaded with cargo to the north, and planes with Soviet crews flew to their territory.

The transportation routes had to be guarded not only from bandits and thieves but also from rebellious tribes that could be bribed by German agents. Through the Persian Gulf and Iran, one branch of the trans-African air route passed into the Soviet Union. Bombers taking off from the United States or fighters assembled in West Africa, through the Black Continent and the Middle East, reached Iran, and from there, it was just a stone's throw to the Soviet border. Working at assembly plants located in southern Iran or Iraq required maximum effort from local workers, American and British engineers, Soviet pilots, drivers, and commissioning staff. Often, work had to be done from 3-4 am until 11 am. Later, the metal heated up so much that burns could occur. After passing through Iran, the cargo was delivered to the Soviet Transcaucasia or Central Asia. A significant portion was transported by ships across the Caspian Sea, and when the front retreated westward, further along the Volga. The joint efforts yielded results without delay. In August 1941, through the "Persian corridor," only 10,000 tons of cargo could be transported per month. By October 1942, it reached 30,000 tons of cargo, and by May 1943, it reached up to 100,000 tons per month. The downside of the Trans-Iranian route was that ships from the US East Coast took about 75 days to reach the ports of the Persian Gulf via Africa, and then additional time was required to deliver the cargo to Soviet territory.

Between the USSR and the USA, an air route was established, named the Alaska-Siberia (AlSib) route [18:519-543]. The decision to organize it was made by the Soviet side on October 9, 1941, and the movement began on October 6, 1942. Throughout the war years, 7908 aircraft arrived from the USA to Krasnoyarsk. In Fairbanks (Alaska), Soviet pilots received planes from the Americans and flew them across the Bering Strait to the airfield in Wellekale, where they were relieved by pilots of the next night-flight squadron. Through this relay method via Chukotka, Kolyma, and Yakutia, the aircraft reached Krasnoyarsk (a total of about 6,500 km). At each stage, pilots were transported back on transport aircraft. The most experienced pilots were selected for ferrying the aircraft, as flights took place in extremely challenging natural and climatic conditions: rain, snow, fog, smoke from forest fires, severe cold, strong winds, and low clouds. The planes became ice-covered, magnetic compasses functioned poorly, and there were no accurate maps. Underneath the aircraft's wings were endless tundra, taiga, and mountains, and they had to reach the next airfield no matter what, as otherwise, death was almost inevitable. It's not surprising that on the Soviet section of the air route, 81 aircraft were lost (according to other data - 44), and 115 Soviet pilots perished. On the American segment, 68 aircraft were lost. From the Pacific Ocean, American cargo could reach Arkhangelsk and Murmansk via the Northern Sea Route, and along the way, some of it was diverted for the needs of Siberia and the AlSib route. However, the scale of transportation on this route through the Soviet Arctic was small for obvious reasons. At the very end of the war, when the German fascist occupiers were expelled from Crimea and Ukraine, a route through the Black Sea opened. In early 1945, the first ships with lend-lease cargo arrived in Odessa, which would have likely gone through the Persian Gulf earlier. But the war soon ended.

As for what and how much was delivered via lend-lease?

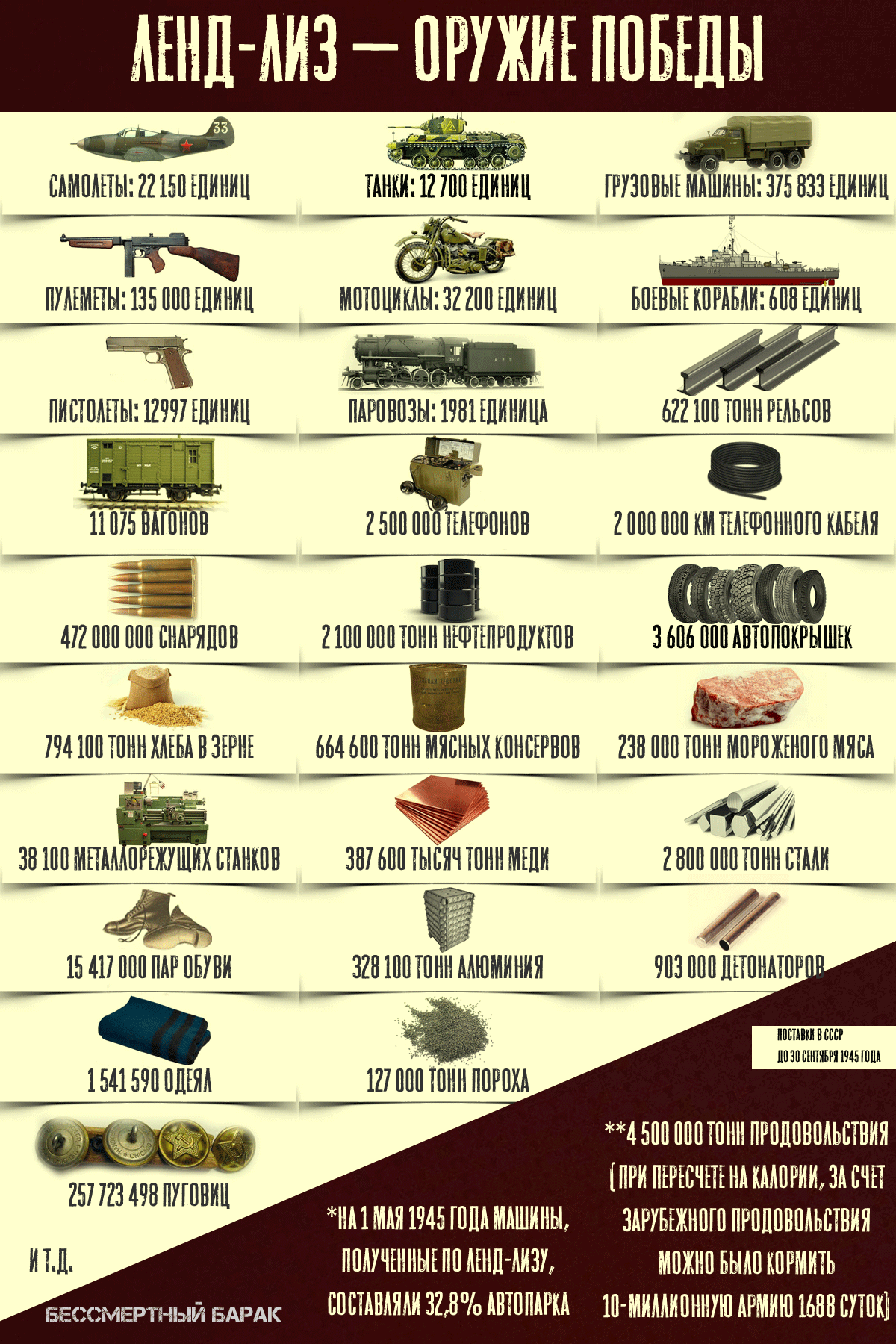

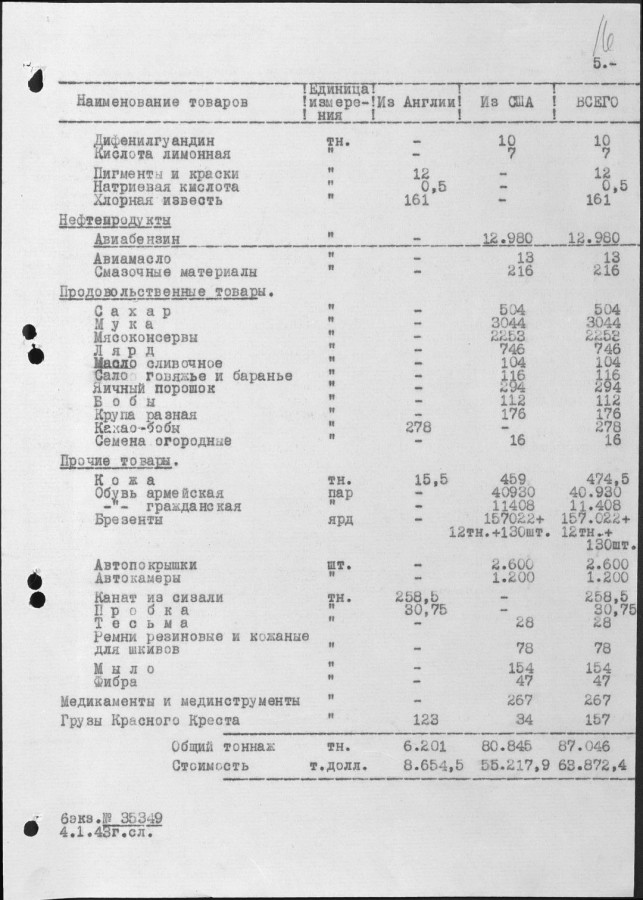

You can quickly list all deliveries in tons, or you can examine them in more detail. In these figures, you can see not only tanks and airplanes but also ordinary household items: blankets, buttons, shoes, food. Most debates about the role of lend-lease on the Soviet-German front boil down to counting the number of "Shermans" or "Airacobras," while deliveries of nearly 500,000 vehicles, from motorcycles and command "Jeeps" to 20-ton tank trailers, which made the Red Army many times more mobile, are usually overlooked. It's difficult to overestimate the deliveries of just 100,000 three-axle "Studebakers" alone — by the second half of the war, the army was saturated with them. In the photo, one of the RKKA bases, where trucks are awaiting shipment to the front, spring 1944, below is a list of some of the lend-lease program deliveries.

22,150 aircraft (including 5,000 P-39 Airacobras fighters). A total of 9,500 were produced, meaning more than half were supplied to the USSR. This is one of the best fighters of World War II. Pokryshkin flew the Airacobra from 1943 onward.

12,700 tanks were supplied, including 918 British Army Matilda II infantry tanks (1084 dispatched), 3664 American M4A2 Sherman medium tanks (4102 dispatched), and 3332 British infantry tanks (3782 dispatched, representing 46% of all produced, with half assembled in Canada).

1800 self-propelled guns (as of November 30, 1944)

7944 (according to other sources, 8218) anti-aircraft guns

4912 anti-tank guns

135,000 machine guns

12,997 pistols

3300 armored personnel carriers

5500 artillery tractors

8071 tractors

375,833 trucks (as of May 1, 1945, vehicles received through Lend-Lease made up 32.8% of the Red Army's fleet)

3,606,000 tires (according to other sources, 3,786,000) (43.1% of Soviet tire production)

51,000 jeeps

8000 tractors

32,200 motorcycles (according to other sources, 35,170) (1.2 times more than Soviet motorcycle production)

472,000,000 shells

281 military ships

128 transport ships

3 icebreakers

35,800 radios

9351 fighter radios

2,000,000 kilometers of telephone cable

2,500,000 telephones

200 telephone exchanges

445 (according to other sources, 348) locators

1981 locomotives (2.4 times more than Soviet locomotive production from 1941-1945)

66 diesel-electric locomotives (11 times more than Soviet production)

11,075 wagons (10 times more than Soviet production from 1942-1945)

622,100 tons of rails (56.5% of Soviet rail production from 1941-1945)

2,100,000 tons of petroleum products

628,400 tons of aviation gasoline +

732,300 thousand tons of light fraction gasoline (total Lend-Lease aviation gasoline deliveries exceeded Soviet production by 1.4 times)

1,200,000 tons of chemicals and explosives

127,000 tons of gunpowder

903,000 detonators

387,600 thousand tons of copper (82.5% of Soviet copper production during the war)

328,100 tons of aluminum (1.25 times more than Soviet aluminum production)

2,800,000 tons of steel

38,100 metalworking machines

15,417,000 pairs of shoes

1,541,590 blankets

257,723,498 buttons

4,500,000 tons of food (according to calculations by Professor M.N. Suprun, who recalculated food supplies by calories, foreign food supplies could feed a 10-million-strong army for 1688 days), including:

49,490 tons of wheat

238,000 tons of frozen beef and pork

624,000 tons of sugar

81,004 tons of butter

307 tons of chocolate

664,600 tons of meat preserves (108% of the total canned meat production in the USSR)

331,066 liters of alcohol

and 2,500,000 tons of other goods.

A toast to lend-lease

The Tehran meeting of the leaders of three allied countries — the Soviet Union, the United States of America, and Great Britain, held in Tehran from November 28 to December 1, 1943, is one of the key diplomatic events of World War II. For the first time, the leaders of the "Big Three" met to discuss and implement important war and peace issues. The conference had a positive impact on the intergovernmental relations of the alliance, increasing trust and mutual understanding in the anti-Hitler coalition.

In post-war American and Soviet literature, the Tehran Conference was extensively documented: memoirs of the meeting's participants, collections of documents with protocols of conversations and sessions were published. However, they became available to the public only after 1961 due to an agreement among the heads of the allied states not to disclose the documents. According to the translator from the Soviet side, Valentin Berezhkov, the United States was the first to break the silence by publishing in 1961 a collection of diplomatic documents "Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, the Conferences at Cairo and Tehran, 1943." In response, part of the documents of the Tehran Conference was released in the USSR, which were published the same year in the journal "International Life." Six years later, they were published as a separate collection called "Tehran – Yalta – Potsdam," which later underwent two more editions.

Later in the USSR, a multi-volume work "The Soviet Union at International Conferences during World War II, 1941-1945" was published, with volume 2 entirely dedicated to the Tehran Conference. It should be noted that when creating this six-volume edition, the compilers used the aforementioned American collection of diplomatic documents, but not all descriptions of the meetings of the leaders of the three allied countries were included in the Soviet collection. For example, the documents for November 30, 1943, contain records of meetings in the following order:

meeting of Stalin and Churchill at 12:40;

meeting of Molotov, Eden, and Hopkins at 13:30;

meeting of the heads of state during lunch at 13:40;

the third meeting of the heads of the allied states from 16:30 to 17:20.

But the Soviet collection omits one more event of that day — the festive dinner in honor of Winston Churchill's 69th birthday, which took place from 20:30 and ended closer to midnight. At this event, in addition to the birthday boy, Stalin, and Roosevelt, almost the entire key composition of the delegations of the allies was present. It was at this dinner that Stalin made the designated toast, emphasizing the significant role of lend-lease for the Soviet Union in the war.

For the Soviet reader, Stalin's speech remained an open secret. Stalin's speech cannot be found in any of the published collections of documents in the USSR. Information that Stalin made the toast can, however, be found in the memoirs of some participants of the banquet. These memoirs were published in the USSR but underwent censorship, ultimately altering the essence of the speech. A prime example is the Soviet edition of "As He Saw It," the memoir of Elliott Roosevelt, son of the U.S. President. The book was released in 1946 (translated as "Его глазами" in Russian), detailing the important international meetings of the great powers' leaders, which Elliott attended with his father. A year after its publication, it was translated and published in the Soviet Union. In his book, Elliott Roosevelt dedicates an entire chapter to the Tehran Conference, relying primarily on his own memories and his father's records.

Apparently, this was the first presentation of its kind that shed light on the internal details of what happened in Tehran. The author was a direct witness of Stalin's speech and quotes it directly in the book. In the Soviet edition of 1947, this moment was translated as follows:

"Toasts followed one after another so often that we didn't have time to sit down; as a result, some of us conversed standing. I remember how, in between some two toasts, I listened to Randolph Churchill's thoughts on a very important issue, but I don't remember exactly what it was about. Then there was a moment when the gods of friendliness and joy dozed off, and then General Sir Alan Brooke got up and began to expound on the topic that the English people suffered more in this war than all others, lost more, fought more, and did more for victory. A shadow of irritation passed over Stalin's face. Perhaps it was this that prompted him to get up almost immediately and make a toast.

- I want to tell you what, from the Soviet point of view, the president and the United States have done for victory. In this war, machines are paramount. The United States has proven that it can produce 8 to 10 thousand planes per month. England produces 3 thousand planes per month, mainly heavy bombers. Therefore, the United States is a country of machines. These machines, received through lend-lease, help us win the war."

And now let's turn to the original:

"I want to tell you, from the Soviet point of view, what the President and United States have done to win the war. The most important things in this war are machines. The United States has proven that it can turn out from eight to ten thousand airplanes a month. England turns out three thousand a month, principally heavy bombers. The United States, therefore, is a country of machines. Without the use of those machines, through Lend-Lease, we would lose this war".

To those who speak English, it should be obvious that the meaning has been changed in the last sentence. Let's use Google Translate and get the following: "Without these machines supplied by lend-lease, we would have lost this war."

Moving on to the second source, Stalin's speech is recorded in the daily journal of the President of the United States during the trip to Tehran, and it was published in the American collection of 1961 (page 469). Stalin's speech was entered into the journal as a significant event during the celebratory dinner on the evening of November 30, 1943:

"I want to tell you, from the Russian point of view, what the President and United States have done to win the war. The most important things in this war are machines. The United States has proven that it can turn out from 8,000 to 10,000 airplanes per month. Russia can only turn out, at most, 3,000 airplanes a month. England turns out 3,000 to 3,500, which are principally heavy bombers. Without the use of those machines, through Lend-Lease, we would lose this war".

This record of the toast has several differences from the recollections of Elliot Roosevelt and the Soviet versions. However, it is currently the only one that is documentary confirmed (Google Translate and some editorial adjustments):

"I want to tell you, from the Russian point of view, what the President and United States have done to win the war. The most important thing in this war is machines. The United States has proven that it can produce from 8,000 to 10,000 airplanes a month. Russia can produce a maximum of 3,000 airplanes a month. England produces from 3,000 to 3,500 airplanes a month, mainly heavy bombers. Without these machines supplied by lend-lease, we would have lost this war."

We conclude that Stalin's speech, as translated in Elliot Roosevelt's book in 1947, was altered. Whether this was a gross error by the translators or if the meaning was deliberately distorted for censorship reasons is unclear. However, the Soviet translation made its way into Beria's book, despite a 20-year difference in publications.

Oil in the Lend-Lease system

The German offensive on Stalingrad and the southern regions of the USSR, launched in the autumn of 1942, seriously impeded the supply of Soviet industry and the army with petroleum products. The Baku, Grozny, and Maykop oil regions, which provided 85% of domestic oil supplies, were cut off from the main transportation routes. By this time, due to the threat of the region's capture, the Baku-Batumi oil pipeline had been dismantled, and the export of oil products via the Volga during the Battle of Stalingrad was blocked. During these wartime years, drilling of new wells in the Caucasus was halted, and, moreover, due to difficulties with oil exports, a large number of high-flowing oil wells had to be mothballed. Overall, from the second half of 1942, oil production in the Baku fields - the country's main oil-producing region - decreased by about half.

A significant portion of Azerbaijani oil and refinery plants, along with all equipment and personnel (approximately 10,000 specialists), were relocated to the Volga, Urals, Kazakhstan, and Central Asia regions. This forced transfer of the oil industry to the east led to a significant reduction in oil production in the country, preventing the industry from recovering until the end of the war.

The decline in oil production in the face of rapidly increasing demand for petroleum products led to an "oil famine," which could not but have a negative impact on both the front and the rear. Significant improvement in the fuel situation, overcoming the oil deficit, was achieved through American deliveries under the Lend-Lease program.

Under Lend-Lease, the USSR received 1,320,000 tons of aviation gasoline, of which 1,163,000 tons (88.1%) had an octane rating above 96. In addition, within this program, delivery of light gasoline fractions totaling 834,000 tons was carried out, used in the production of aviation fuel. To this should be added 573,000 tons of aviation gasoline supplied outside of Lend-Lease from oil refineries in Britain and Canada. In total, this amounts to approximately 2,727,000 short tons or 2,479,000 metric tons of aviation fuel.

It should be noted that the imported aviation fuel in the USSR was used for:

1. Supplying English and American aircraft delivered under Lend-Lease, which accounted for about 8-10% of the total demand for this type of petroleum product;

2. Expanding production and improving the quality of Soviet aviation gasoline. Soviet aircraft flew on gasoline with much lower octane numbers, so by mixing domestic and imported gasoline fractions, it was possible to increase the octane rating of Soviet aviation fuel and significantly, by an order of magnitude, expand its production volume.

At the beginning of the war, a formulation for compounding with imported high-octane components (octane gasoline, iso-octane, alkylbenzene, etc.) was developed at domestic oil refineries. The involvement of light high-octane components in domestic aviation gasoline allowed for the densification of the fractional composition of the base gasoline and thereby increase its production and raw material selection. A State Prize was awarded to a group of Baku scientists and specialists, including V.S. Gutyr, M.A. Gorelik, L.B. Samoilov, and others, for the development and implementation of the aviation gasoline compounding scheme.

Lend-Lease in Documents

Main Sources:

1. Great Patriotic War. Jubilee Statistical Compilation: Stat. collection / Rosstat. — Moscow, 2020. — 299 p.

2. Stettinius, E. Lend-Lease - the Weapon of Victory. Appendix. The Role of Lend-Lease in the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945.

3. Ryzhkov, N.I., Kumanev, G.A. Food and other strategic supplies to the Soviet Union under Lend-Lease 1941-1945.

4. Monin, S.M. World War II. Myths about Lend-Lease / Journal "People and Texts. Historical Almanac."

5. Butenina, N.V. Lend-Lease: The Deal of the Century. Moscow, 2004.

6. Roosevelt, E. As He Saw It. – Moscow: IIL, 1947.

7. Sherwood, R. Roosevelt and Hopkins Through the Eyes of a Witness. – Moscow: Foreign Literature Publishing House, 1958.

8. Jones, R. Lend-Lease. Roads to Russia. US Military Supplies to the USSR in World War II – Moscow: Centrpoligraf, 2015.